The person who saved humanity from plague and cholera

On 15 March 1860 in Odessa, the brilliant epidemiologist Waldemar (Vladimir) Haffkine was born

He was a pupil of Ilya Mechnikov and Louis Pasteur. He invented vaccines against plague and cholera and tested them on himself. He saved millions of people. India considers him to be a national hero, and the Queen Victoria gave him one of the highest awards of the British Empire. 155 years ago, the outstanding bacteriologist Waldemar Haffkine was born.

“The newspapers write a lot about plague in India.

Do you know if our party is for plague or against it?”

Karel Čapek.

The moral code of an A student

The father of our hero worked as a teacher of a state Jewish school. The family was large and poor. So poor that in search of a “cheap” life they had to move from Odessa to Berdyansk. There Waldemar (then known as Markus-Volf) graduated from the cheder and Russian high school. The poet Shaul Chernikhovsky, who was friends with Haffkine in Switzerland, wrote that at home the young Haffkine stood out for his rare persistence and diligence. The boy helped his parents around the house a great deal: he bought coal, heated the stove, tidied the rooms and even cooked.

Waldemar studied brilliantly and inspired others to study. “There was not a single lazy-bones or scallywag who did not come under his influence,” Chernikhovsky recalled. One of Haffkine’s nephews claimed that he was the only person who did not yield to his uncle, who “bit his nails in despair that he could not make me study.”

In his childhood, Haffkine made a moral code for himself. Its main points were:

1. always be the leader;

2. don’t gossip;

3. keep a secret;

4. keep your promises.

The revolutionary and pupil of Mechnikov

In 1879 Waldemar graduated from high school and enrolled in the Novorossiisk University in Odessa. His father could not provide a kopeck for the talented boy’s education. The situation was saved by his elder brother, who provided 10 rubles a month, and 20 kopecks a day for meals was provided by the university. This was enough money not to starve, and Waldemar immersed himself in study with youthful passion. Ilya Mechnikov noticed the capable boy. Unfortunately, he was not the only one to notice him.

Colonel Pershin mentioned Haffkine in his first year of study on the “List of politically unreliable persons”. The gendarme wrote: “All the students listed belong by their political views to the so-called “Black Boundary” party. This information was gained by agents, but the source proved correct himself in relation to Matveevich, Haffkine, Romanenko and others.”

The American historian Patricia Herlihy wrote that the center of revolutionary propaganda in Odessa was not the university, but the school of apprenticeship for poor Jews, “Labor”. By this period Jews made up a third of the residents of Odessa, while many of them were Russified and had assimilated to Russian culture. But this did not save them from pogroms.

In 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. Rumors immediately spread that Jews were to blame, and that there was an order to destroy Jews’ property. A wave of pogroms spread through the south of the empire, and on 3 March it reached Odessa. The newspaper “Odessa Herald” reported. “Rioters tear dresses to shreds. The crowd looking on, 20% of which are well-dressed people, laugh as they watch…” The authorities tried to deal with the rioters with paternalistic exhortations, which naturally did not help. And the interior minister Ignatiev blamed the violence on the Jews themselves – they worked too successfully, traded and “exploited” the local population. The Jews of Odessa began to unite in groups of self-defense. Students also joined these divisions regardless of their ethnicity and religion. Street fighting broke out. The police did not detain the looters, but the Jews who were defending themselves. During a fight, Waldemar Haffkine was caught carrying a revolver. In fact, during his time at university he was arrested twice. He was saved by Ilya Mechnikov, who highly valued the talented pupil. But the second time he could not save Haffkine from expulsion from university. However, Haffkine abandoned revolutionary activity after his comrades began to resort to terror. Private lessons, work at the zoological museum of the university, passing exams and defending his dissertation – all of this absorbed the young scientist.

Paris: “Bravo to the Russian doctor!”

In 1885, the Paris journal “Annals of Natural Sciences” published Waldemar Haffkine’s dissertation. The university board invited him to take the position of lecturer – on condition that he convert to Christianity. Haffkine refused and left the country. Initially to Switzerland, where he became a lecturer at Lausanne University. And then Ilya Mechnikov, who already worked at the Pasteur Institute himself, helped Haffkine to move to Paris. Waldemar became… a junior librarian. During the day he did his official work duties, and early in the morning and after work, he conducted experiments at the institute laboratory.

By that time, the German scientist Robert Koch had discovered that the catalyst of cholera, Vibrio cholerae, was a bacterium resembling a comma. The French genius Louis Pasteur made the first vaccinations against anthrax and rabies, laying the foundations of vaccination. Waldemar Haffkine began to develop an anti-cholera serum. In 1892, he tested the serum on guinea pigs. And then on himself. It was successful. Pasteur and Mechnikov congratulated the young scientist. The French newspaper wrote: “Bravo to the Russian doctor!” Haffkine offered his invention to Russia, but his help was rejected because of his “revolutionary” reputation, and just as “revolutionary” a discovery. The vaccine was also rejected in Spain and France. Many doctors declared that the idea of vaccination was dangerous.

On Her Majesty’s service

On 20 November 1892, Louis Pasteur wrote in a personal letter: “Haffkine has been in London for a week, where he is trying to get permission to go to Calcutta from the English authorities, in order to conduct experiments there which he intends to carry out in the Kingdom of Siam.” India was the traditional breeding ground of cholera. In 1893, the state bacteriologist of the British crown Waldemar Haffkine arrived in Calcutta.

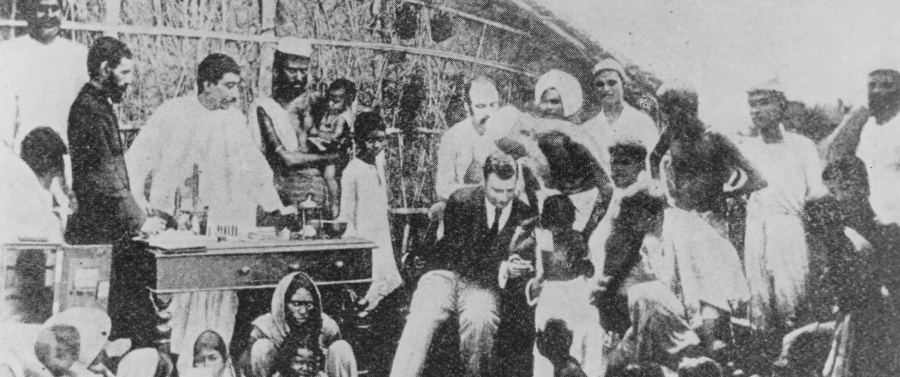

It was spring in India. The inhabitants of a small village were dying from cholera. At the height of the epidemic, doctors arrived: four Indians and one white man. They offered the peasants salvation: vaccinations. The peasants hadn’t heard of vaccinations, they took white people for English, and the issue of recovery they usually entrusted to higher forces. They threw rocks at the uninvited guests. Suddenly among the shouts and hubbub, the white man stood up and raised the hem of his shirt. His colleague quickly prepared a needle and made an injection. The crowd fell silent. The other doctors also took their shirts off and gave each other injections. In the silence, an Indian doctor explained that the white doctor was not English, but Russian, and that the vaccination was the only salvation from cholera. 116 of the 200 inhabitants of the village agreed to the injection. Subsequently not a single person who was injected caught cholera, although it came to the village nine more times. Thus for the first time in the history of the battle against cholera, the vaccination was used that was invented by the Odessan Waldemar Haffkine.

Two years after Haffkine came to India, the mortality rate from cholera dropped by four times. He spent a total of 22 years in the country. He injected around 25,000 people personally.

“…A ordeal by work and fear”

In 1896 a plague epidemic broke out in Bombay. At the request of the authorities, Haffkine went to the city and in three months prepared an anti-plague vaccine, which he tested on himself. Many years later, the renowned Indian scientist, Professor Kanalkar, who studied the history of the development of medicine in his native city, wrote: “The epidemic was constantly growing. Doctor Haffkine was in a great hurry. At the same time he prepared the vaccine, he gave numerous lectures for doctors who were studying to battle the plague. This reserved and taciturn gentleman became incredibly eloquent when he had to teach someone the basics of battling the plague. He worked 12 to 14 hours a day. One of his assistants fell ill with a nervous disorder. Two left, not enduring the ordeal by work and fear.”

An Indian stamp with a portrait of Waldemar Haffkine

“Plague is not so terrible,” wrote Anton Chekhov. “We already have vaccines that are effective, which by the way we owe to the Russian doctor Haffkine. In Russia he is completely unknown, but in England he had long been called a great philanthropist. The biography of this Jew, so hated by the Indians, who almost killed him, is quite wonderful.”

The legacy of Doctor Haffkine

At the Jewish University in Jerusalem, the archive of Doctor Haffkine is preserved. When the writer and journalist Shulamit Shalit decided to investigate it, she was amazed by the broadness of the scientist’s interests. “It turned out the Haffkine wrote all his life, and not just a diary, and not just scientific reports. For example, his work: 'The teaching of Schopenhauer. An attempt of popularization in the history of philosophy,'" Shalit discusses the documents. “He wrote a note for himself: 'familiarize yourself thoroughly with the encyclopedia of law and the history of it, with the spirit of oriental languages – Jewish, Arabic and Sanskrit.' Here is a manuscript on the difficulties of income tax. Note to Balzac’s works in French! There are notes showing that he studied Dutch.” And he also has letters from Rothschild, Herzl, Dizengoff.

In 1915, Waldemar Haffkine stopped his work in science, and settled in Switzerland, where he immersed himself in the study of the Torah and Talmud. He believed that only religion preserved the Jewish people, and that a Jewish state should be founded in the 20th century.

In 1920, Waldemar Haffkine became a member of the central committee of the International Jewish Union (Alliance), which was responsible for charity and enlightenment work. By the order of Alliance, Haffkine visited the Jewish colonies of Ukraine, Russia, Poland, Belarus and Germany. The archive contains a report about connections with yeshivas in Poland, Lithuania and Hungary.

When he returned from his journey, Haffkine liked to tell one story: “In Russia I was accompanied by Reuven Brainin and his wife. When we went to one Jewish agricultural colony, to my great regret, I found that the main source of its income was breeding animals whose meat the Jewish religion forbids to eat… Many members of the colony came to see us, surrounding our car. I saw that Brainin, according to the local custom, was kissing the head of the colony. After he kissed Brainin, this young farmer wanted to kiss me as well. But I limited myself to a handshake, saying: “I don’t wish to be kissed by lips tainted with pork.”

In Israel, in the area of the John F. Kennedy Memorial, the Haffkine grove can also be found on one of the hills of Jerusalem. In Odessa there is a Waldemar Haffkine street. In Mumbai, the largest scientific research center in Southeast Asia is named after Doctor Haffkine. The center works in the fields of bacteriology and epidemiology, and grew from the small laboratory founded by the Russian scientist in 1896.

Doctor Haffkine never started a family, and he once admitted to his friends that he was afraid to leave his wife a widow in a dangerous region. The scientist died in Lausanne in 1930. He bequeathed his belongings to pupils of Jewish religious schools, with the wish that they would also study natural sciences.

Подпишитесь на рассылку

Получайте самые важные еврейские новости каждую неделю